Recent social theory dealing with modernity has focused on the increase of new forms of risk as a social challenge. The growing relative importance of manufactured risks (that are the product of human activity) as compared to external or natural risks is well described in the work of the sociologists Ulrich Beck (Beck, 1992) or Anthony Giddens (Giddens, 1990).[1] The emergence of new forms of manufactured risk (e.g. environmental risk, financial risk) is a direct consequence of rising levels of complexity and interconnectedness in industrial societies, reflected in the organization of production, the nature of the technologies employed, etc.

When such risks are realized they can become catastrophes. There is unfortunately no shortage of recent man-made catastrophes (the Chernobyl disaster, Fukushima, the recent financial crisis, etc.) to illustrate this point. The vulnerability of individuals which results from the allocation of new forms of risk is a key social challenge. Beck in his discussion of the risk society has argued that the distribution of risk, rather than wealth, is the central social issue in modernity.

The idea that human beings need not be passive in the face of nature, but that the future can be made predictable with probabilistic calculations, is a move “against the gods” (to borrow the title of Peter Bernstein’s book[2]), with the development of probability and statistical analysis allowing humans to shape their own future rather than passively await their fate. Beck summarizes: “Risk makes its appearance on the world stage when God leaves it. Risks presuppose human decisions.” (Beck, 2006: 333). Risks can be understood, measured, and converted into “risk-taking”, arguably one of the drivers underlying scientific and economic progress.

Modern techniques for quantifying risk are also at the core of modern finance. The Von-Neumann-Morgenstern (VNM) expected utility framework outlined in MWG, Ch. 6 is risk-based in that it assumes a well-defined event space (a set of possible outcomes) with known probabilities (the formal concept of the lottery representation, with a list of probabilities assigned to all outcomes in the event space).

Though many experiments have shown that individuals tend to display behavior that is frequently inconsistent with expected utility, thereby invalidating the theory as a positive description of choice behavior, the framework is analytically convenient and (arguably) has normative merits as a guide to decision-making in the presence of risk.

The standard approach to risk assessment has given rise to a whole range of risk analysis techniques and models, all of which assume risk to be well defined. Techniques for risk management are based upon the view that it is possible to assign probabilities to potential outcomes.[3] This in turn is based upon the characterization of probabilities as a degree of rational belief capable of measurement, for instance as the ratio of the number of outcomes of a specified type to the total number of outcomes, or the statistical frequency of a particular outcome (frequentist approach). In this sense, probabilities are objectively known as a property of a particular state of the world.

The concept of Bayesian inference allows for a different interpretation of the concept of probability, mainly that of a degree of belief rather than an objective property of a particular system. Bayesian probabilities are conditional upon prior knowledge and experience, and can be revised as beliefs get updated.

There are different schools of thought in this regard. The subjectivist school views probabilities as representing warranted personal beliefs, whereas the objectivist school attributes a stronger basis to the belief as the only conclusion sustained by rational inference.

The Triumph of Risk Over Uncertainty

The risk framework is fundamentally different from one which recognizes real uncertainty, where knowledge of the future cannot be based on probabilistic calculus. In economics the distinction between risk and uncertainty was first explored by Frank Knight (Knight, 1921/2006).

Knight distinguishes between forms of indeterminacy that are predictable and lend themselves to probabilistic calculation (risk), and forms of indeterminacy that entail an inability to assign probabilities to various potential outcomes of a given situation. This could be because it is impossible to identify all possible outcomes (there are unknown unknowns), or because although all event alternatives are known, probabilities cannot be computed (unknown knowns?).[4] In those situations, there is no scientific basis to apply probabilistic calculus to form expectations of the future.

J.M. Keynes was perhaps the first economist to grasp the full significance of radical uncertainty for economic analysis. Author of A Treatise on Probability published in 1921, Keynes developed the view that it is not always possible to assign a numerical value to probabilities — a point unrelated to the practicality of measurement (Keynes, 1921). The frequentist approach breaks down in some situations. It is impossible to find strictly relevant frequency ratios because even if a relevant statistical database were to exist, the presence of additional information might make the database inadequate for the computation of a numerical probability.

In his Treatise, Keynes gave the example of the outcome of a Presidential election, or something as ordinary as the probability that we reach home alive if we are out for a walk. In a famous later article, he gave the example of “the price of copper and the rate of interest twenty years hence” (Keynes, 1937). The implication for Keynes’ General Theory was that macroeconomic variables such as investment and consumption are shaped by many factors which are not susceptible to probabilistic analysis (fundamentally different from the outcomes of a game of roulette).

Events determined by human decisions (much of which, he argued, are driven by ‘animal spirits’ – ideas and attitudes determined by intangible psychological motivations) do not lend themselves to the calculation of probabilities. We can think of many events that are likely to influence economic variables (such as prices and incomes) and economic decisions (such as the level of investment) but are by their very nature radically uncertain, such as the occurrence of wars, changes of government, inventions, climatic changes.

Yet this insight was completely neglected in the mainstream economics that followed (and arguably marginalized by Keynes’s own mainstream interpreters, such as J.R. Hicks). The notion of calculable risk has permeated modern microeconomics, starting with its formalization in the concept of ‘expected utility theory’ introduced by J. von Neumann and O. Morgenstern in 1947. There has been a triumph of risk over uncertainty (Reddy, 1996). It is something of an irony of history that the importance of the incalculability of risk was first explored in a discipline which has since failed to take the insight into account. This irony is not lost to other social scientists:

“The discovery of the incalculability of risk is closely connected to the discovery of the importance of not-knowing to risk calculation, and it is part of another kind of irony, that surprisingly this discovery of not-knowing occurred in a scholarly discipline which today no longer wants to have anything to do with [it]: economics.” (Beck, 2006: 334).

In this respect, the presentation of the topic of choice under uncertainty in MWG Ch. 6 is emblematic of the triumph of risk over uncertainty in the body of modern microeconomics. The chapter begins with a framework in which the set of possible outcomes and corresponding probabilities are already known, i.e. a framework of risk rather than uncertainty: “we begin our study of choice under uncertainty by considering a setting in which alternatives with uncertain outcomes are describable by means of objectively known probabilities defined on an abstract set of possible outcomes.” (Ch.6: 167).

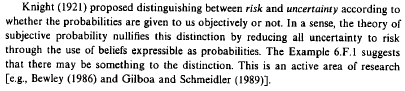

Further, MWG loosely uses the terms of risk and uncertainty interchangeably throughout the chapter, so that the distinction between the two is not explicitly acknowledged until the very end. Even so, it is a somewhat cautious acknowledgement:

Though in this paragraph MWG does acknowledge that the topic of uncertainty is an active area of research, it is introduced as a somewhat marginal topic, which may or may not be relevant to economic modeling. The text contends that subjective expected utility, by permitting an “as if” interpretation of observed behavior assuming that choices conform to the axioms of VNM expected utility theory, thereby reduces situations of uncertainty to situations of risk (probabilities are simply inferred from observed choices).

However, the illustrative reference to Example 6.F.1. (the Ellsberg paradox) seems to indicate that the claim that subjective probability theory might nullify the distinction between risk and uncertainty is premised on the unstated idea that the use of expected utility theory is primarily descriptive (for which reason the finding of the paradox commands attention). Both expected utility and subjective expected utility are certainly jeopardized as a result of empirical violations (such as the Ellsberg paradox) of the axioms of expected utility theory, to the extent both approaches presuppose that observed choices (whether understood in terms of assumed or imputed probabilities) are compatible with such axioms.

However, whether or not individuals acted in such a way, the distinction made by Knight and underlined by Keynes would remain pertinent to how we should make decisions and comport ourselves in the face of fundamental uncertainty.

Why Uncertainty Still Matters In The Risk Society

The recent social theory dealing with the risk society and modernity stresses that a key characteristic of modernity is the incalculability of the consequences of increasingly prevalent forms of socially created risk. This is in part due to the complexity of causal chains, the remoteness of consequences when there is a latency period (e.g. with nuclear waste, or climate change), non-linear dynamics (e.g. tipping-points), etc.

Probabilistic calculations cannot accurately be made, because ex ante the event space cannot be adequately outlined, probabilities cannot be easily assigned, and the impact of actions upon likelihoods is obscure. In the risk society, radical uncertainty is ubiquitous, and true situations of risk confined to casino tables: “the unknown and unintended consequences come to be a dominant force in history and society” (Beck, 1992: 23).

How individuals ought to behave in situations of true uncertainty (especially in light of the potential for catastrophes) becomes a key issue - arguably one that cannot easily be approached in the standard frame, including expected utility theory. Here we should take the time to untangle a few separate assumptions of the VNM expected utility framework: 1) the set of possible outcomes is known, 2) numerical probabilities assigned to each outcome are objectively known, 3) preferences over lotteries satisfy some key axioms (independence and continuity).

In situations of true uncertainty, the first two assumptions are especially controversial. First, if there are unknown unknowns, the set of possible outcomes cannot be known. Second, it is possible to interpret probability in terms of subjective belief (as in the Bayesian approach) and defend the applicability of expected utility theory on the basis that it always ought to be possible to form an opinion regarding the degree of likelihood of an outcome. However, one might object that this is missing the point altogether that the identification of a well-defined probability distribution is not straightforward in situations of uncertainty.

Leaving aside the VNM expected utility framework, the recent example of the 2007-2008 financial crisis jumps to mind. Models used in risk management, which were heavily reliant on probabilistic calculations (and well-defined probability distributions) failed spectacularly. This is true of many financial institutions that took large risks they did not fully understand when investing in complex products, as well as credit rating agencies that gave favorable ratings to securities that turned out to be quite risky.[5] Mortgage default rates (and complex phenomena such as default correlation) and the evolution of housing prices (both important drivers in the pricing of securitized products like mortgage backed securities) were not properly understood nor modeled.

The flawed assumption of normal distribution of data made risk models particularly vulnerable to unpredictable and consequential events (“black swans”).[6] In AIG’s case, for instance, the valuation process for the Credit Default Swaps (“CDS”) portfolio relied upon models[7] that ascribed an (in retrospect) unrealistically low probability of default to underlying securities being insured, attempting to price the value of the degree of correlation of default between the underlying mortgages.[8]

Moreover, these assumptions were ‘sold’ to others as being justified by sophisticated quantitative modeling based on historical assumptions. There could at present be few more relevant examples of the difficulties (and danger) of identifying what probability distributions to assume in causally complex situations.

A Discourse for Legitimizing Business Decisions.

These considerations lead us to a digression. If the claim that all forms of indeterminacy can be quantified and managed is an epistemic fallacy, how do we explain the widespread acceptance of the risk management paradigm on Wall Street (and specifically the existence of well-defined probability distributions), where ‘real money’ is at stake (and seemingly there should be high incentives for ‘getting it right’)? If social theory has identified fundamental uncertainty as a central issue in modernity, why have the fields of finance and economics not followed suit?

One possible explanation is that of the imperatives of the business context: the high degree of confidence placed in the concept of risk (indeterminacy that can be controlled and measured with probabilistic models) has served as a convenient discourse for legitimizing business decisions (in the process lulling consumers and generating lofty bonuses for management).

Acknowledging to investors that some forms of indeterminacy are not predictable (for instance that AIG could not properly value its CDS portfolio and associated liabilities) might be interpreted as a sign of weakness on the part of management, to be frowned upon by investors. Such admissions are not routinely done.

Yet the presence of radical uncertainty increases the need for the quality of judgment calls used in decision-making. It could be argued that it is precisely because there is radical uncertainty that reliance on the skills and expertise of management is increased, justifying their remuneration (and that of those who place capital at risk)! [This was in fact the motivation for Frank Knight to propound his original distinction, as he wished to reject the idea of normal profits in order to argue against the then popular idea of a tax on supernormal profits, arguing instead that all profits were a reward to entrepreneurs for contending with fundamental uncertainty].

Incidentally, we note that an added issue is that executive compensation on Wall Street is not often based on a risk-adjusted measure of firm profit (a misnomer since we have just made the point that firm profits may be subject to forms of indeterminacy that are not quantifiable – the point here being that executives do not have much to lose if short-term profit is boosted by taking risks which cause adverse consequences in the future).[9]

At AIG, top executives still received high bonuses even when the company lost over $5 billion in the final quarter of 2007 (losses attributable to its Financial Products Division, the division which issued about $527 billion of CDSs).

Ultimately, poor risk management is treated merely a bad business decision, and executives do not go to jail for making bad business decisions. Unless there is a failure to comply with securities law, or actual fraud, it is difficult to recover prior bonuses on the basis of profits that did not take into account the increase in the risk profile of the institution.[10] There might not be such high incentives for “getting it right” after all.[11]

Choice Under Radical Uncertainty

The problem of making decisions in situations where long-term consequences are unknowable is a key issue in many areas other than finance, such as determining how to deal with nuclear energy, climate change, genetically modified food, the dangers of terrorism, etc. The question of how economic actors do (or should) deal with radical uncertainty is indispensable to understand the world. What can be said on that topic beyond the acknowledgment that “we simply do not know”?

Keynes observed that three tendencies underlie the accustomed psychology of decision making in situations of uncertainty: 1) we assume that the past is a guide to the future, and largely ignore future potential developments of which we know nothing, 2) we assume that the view reflected by the market (observed prices and quantities) reflects correct anticipations of the future, and 3) we disregard our own individual judgments and conform with the behavior of the majority (Keynes, 1937).

None of these propensities provide a sound foundation for decision-making. The result is that opinions are potentially subject to sharp fluctuations. As highlighted by Keynes, sudden and violent reversals of conduct, disillusion, breakdowns in beliefs and consensus, are to be expected.

There are other approaches to decision-making in situations of uncertainty, which one might propose on normative grounds, such as the maximin (one illustration being Rawls’ famous veil of ignorance), or the precautionary principle. [In its various formulations the precautionary principle roughly provides that actions should be taken to avoid severe harms, and specifically that there is a social responsibility on the part of policy makers to protect the public from them, even when conclusive scientific knowledge regarding the likely extent of the harms has not been established, as long as the reason to suspect such harms may occur is sufficiently strong].

Chapter 6 in MWG does not do full justice to these issues. It may suffice to note that the title of “Choice Under Uncertainty” is a misnomer. The treatment of indeterminacy is focused on the probabilistic risk framework, with true uncertainty coming up as an afterthought, and even then being inadequately acknowledged. Nietzsche may have said it best:

“Oh heaven over me, pure and high! That is what your purity is to me now…that to me you are a dance floor for divine accidents, that you are to me a divine table for divine dice and dice players. But you blush? Did I speak the unspeakable?”

Also Sprach Zarathustra, Third Part, Before Sunrise.

References:

Beck, U. (1992), Risk Society. Sage: London

Beck, U. (2006). Living in The World Risk Society. Economy and Society, 35(3): 329-345.

Bernstein, P. (1998). Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk. Wiley

Dequech, D. (2000). Fundamental Uncertainty and Ambiguity. Eastern Economic Journal 26, 1 (2000), 41-60

Dequech, D. (1999). Expectations and Confidence under Uncertainty. Journal of Post-Keynesian Economics 21, 3 (1999), 415-430

Giddens, A. (1990). The Consequences of Modernity. Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA

Keynes, J.M. (1937). The General Theory of Employment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 51(2): 209-223.

Knight, F. H. (2006) [1921]. Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit. New York: Cosimo Classics.

Reddy, S. (1996). Claims to Expert Knowledge and The Subversion of Democracy: The Triumph of Risk Over Uncertainty. Economy and Society, 25(2): 222-254

Stiglitz, J. (2010), Freefall: America, Free Markets, and the Sinking of the World Economy. W. W. Norton & Company: New York.

Taleb, N. (2007). The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. Random House: New York.

Tett, G. (2010). Fool’s Gold: The Inside Story of J.P. Morgan and How Wall St. Greed Corrupted Its Bold Dream and Created a Financial Catastrophe (Reprint edition). Free Press; New York.

[1] One could also mention here the work of Scott Lash or Bruno Latour.

[2] Bernstein (1998).

[3] Most applied models for risk assessment in finance are based on a historical simulation of past risks and returns, and make simplifying assumptions about the real world, such as the normal distribution of returns.

[4] We could further distinguish between two kinds of uncertainty, which David Dequech identifies as ambiguity and fundamental uncertainty. Ambiguity refers to situations where relevant information exists at the time the decision is made. Hence the situation could potentially be characterized as risk if the decision-maker could acquire this information. Fundamental uncertainty is altogether different. Essential information about future events simply does not exist and cannot be inferred from any data set (Dequech, 1999 and 2000). In physics, for example, one can distinguish uncertainty arising from lack of information or difficulty in generating a predictive model on the basis of the information we have (e.g. about the likely trajectory of a comet or the weather one month hence) from uncertainty which is in the very nature of things (e.g. quantum effects).

[5] While investments holding Triple A ratings traditionally have had a less than 1 percent probability of default, over 90 percent of Triple A ratings assigned to Mortgage Backed Securities (MBSs) and Collateralized Debt Obligation securities issued in 2006 and 2007 had to be downgraded to junk status shortly thereafter.

[6] Nassim Taleb’s entire semi-popular book The Black Swan (Taleb, 2007) is devoted to this very point, advocating for a greater degree of humility on the part of risk analysts.

[7] AIG apparently used a valuation model originally developed by Moody’s in 1996, the Binomial Expansion Technique model.

[8] A proper assessment of AIG’s exposure to the sub-prime market would have required a different valuation of the CDS positions on AIG’s portfolio. Yet building a fair value assessment is extremely difficult when there are few market comparables due to the highly customized nature of derivative contracts. There were also no observable market comparables for pricing the degree of default correlation.

[9] Recently, we saw executives of major collapsing financial institutions (AIG, Lehman, etc…) walk away with millions of dollars in compensation, refusing to accept any blame for improper risk management of their institutions. See for instance Tett (2010), or Stiglitz (2010).

[10] To date, there has not been evidence of AIG fraudulently misleading investors to the extent that no clear legal accounting violations could be established — AIG’s valuations did not breach any corporate accounting standards for balance sheet reporting.

[11] The provision in the Dodd-Frank Act regarding mandatory clawback clauses in executive compensation contracts, and recent discussion regarding how strictly this requirement should be implemented, is on point